Whilst naturally getting caught up in Jonah’s distress & pain (link) I had forgotten that the bully(ies) is(are) also in need of support – albeit from an angle that’s perhaps not immediately appreciated.

The thoughts in this article come from a psychodynamic understanding of individuals’ psychology and from a systemic understanding of relationships through my practice as a counsellor/psychotherapist.

Why might a bully bully?

I’d suggest that bullying occurs due to the bully’s projected hatred/disgust of themselves.

As we are all people who need to be loved, cared for, taken care of etc, we don’t like to think of ourselves as being someone who is incapable of being loved. Whilst some of us do have these thoughts, others avoid such torturous ideas through a process known as a psychological defence. I’d suggest such a defence’s purpose might be:

…make sure that I don’t know about something that would cause me great pain if I were to become aware of it.

Being an unconscious defensive process, the bully psyche would be using projection to help the bully avoid recognising himself as being the person “in need” of being bullied. I mean ‘in need’ as being the bully’s psyche’s conclusion of what to do with the psychological pain the bully is carrying: destroy.

The bullying process continues whilst the bully’s defence continues to successfully keep the bully from recognising that it is himself he’s attacking through bullying.

I’d suggest this is why, anecdotally at least, it’s said that bullying parents create bullying children – the pain is passed down from parent to child … as is the way to deal with it.

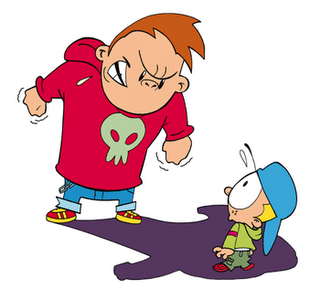

So, bullying is taking place and now we have two people participating in the bullying: the bully (the initiating participant) and the bullied (the unwilling participant). The two have entered into a psychologically torturous relationship.

This relationship is why I suggest that both participants in the bullying are in need of help: the bullied because he (probably) didn’t see it coming, and the bully to help him understand (and then deal with) his own pain.

Like a hook-and-eye closure, both participants have something that makes the bullying relationship succeed; both are contributed (at some level) something to the bullying relationship. The bully contributes something so that he gets to avoid his own pain, and the bullied contributes something for the distress to take root. The bullied acts out the distress that the bully causes (and which may also be the distress that the bully himself is hoping to dispose of – psychologically he’s done it successfully by physical means).

Psychological “Bullying” of the Therapist.

Therapists in the therapy room can also find themselves bullied – but it’s those who work with unconscious processes (psychoanalysts, psychotherapists & psychodynamic counsellors for example) that will struggle use understand their experience of the bullying process (sometimes a very subtle process, not clearly an attack or bullying) to empathically help the bully come to understand what they’re not aware of doing.

Whilst there won’t be physical torture (discharged by the boundaries & contracting at the start of the therapy), through unconscious processes called projective-identification and counter-transference, the therapist can find himself under various forms of mental and emotional attack.

Attack through unconscious processes.

Over my decade+ of work I have found myself:-

- Feeling as if I were going to be physically harmed by a client.

- Have vomited after a client’s session.

- Being continually contradicted, put right, getting the impression I rarely get things right, but the client still comes to sessions.

- Felt attracted to a client that I would not normally have been attracted to, then shortly afterwards feeling rejected (though I have not acted out the attraction).

- Felt inadequate to a client, no matter how I tried to be helpful.

- Whilst listening to a client tell me how wonderful things are in his life, I have felt utter rage and and a sparkling, tingling, need-to-do-something feeling in my arms and wrists.

Just a tiny set of examples – and you may notice how often the word ‘feel’ crops up in these examples where I’ve ‘felt’ that I’m coming off worse as part of the therapy work.

Plus – I’d like to reiterate that these responses, whilst very much in my conscious experience, are hypothetically in response to unconscious material being received from the client. The client isn’t sitting there consciously sending me “be sick” thoughts.

Part of my responsibility as a psychodynamic therapist is to struggle to understand what sort of responses I’m privately having with a client. It is not my usual practice to reveal my responses (my counter-transference) directly – although this can be appropriate too (an article for another time). Instead, I will work privately on understanding my responses, my feelings, so that I might gain an understanding of them in the context of the patient.

If I am feeling as if I were going to be physically harmed by a client, perhaps I am receiving an unconscious communication from the patient – something being communicated about the very real alert about harm.

Sometimes de-attributing ownership of my feelings/thoughts can be helpful: re-framing my fear that instead of thinking…

‘I’m afraid that my client is going to harm me’

…I re-frame this into something like:

‘someone is afraid that someone is going to harm someone’.

This can lead me into wondering if my client is in fear of being harmed by someone – someone else, themselves, me?

Preparing to share an interpretation.

When I’m ready to offer an interpretation of my counter-transference, I find Winnicott‘s ‘spatula’ concept helpful. Donald Winnicott, worked as a paediatrician (and later a psychotherapist) the 1920s to 1970s. He found that when he offered a tongue-depressor (‘spatula’) to a child and allowed the child to discover the spatula for itself, the child would invest more play into the spatula than if Winnicott had indicated the spatula to the child.

When discovered for itself, the child might invest in the spatula becoming an aeroplane, a giraffe, a car … or just something that could be held in the hand and waggled a lot!

When I offer an interpretation of my counter-transference to a client, I allow the client to try and discover the interpretation-meaning for himself (and if he takes no interest I wont force the issue). I might say something like this:

Y’know, I’m a bit puzzled by something; you see whilst I experience a man who seems perfectly capable to take part in the world, you’re effective, you take charge, you get things sorted out, I’m still left with this puzzling sense sometimes of someone who’s… I’m not sure … maybe concerned of being harmed himself? …of being vigilant for attack sort-of-thing?

(I’m aware that my style can sometimes come across a little like stage spiritualists perform: ‘I have the name John – does anyone here have someone called John in their lives…?’ – and perhaps we are using a similar psychological technique of laying out something for someone to discover for themselves).

As I offer my interpretation, as I’m offering my ‘spatula’ to this client, I’m trying to allow him enough space so that he might pick it up and play with it himself. If my counter-transference is accurate (my sense of feeling afraid of being harmed) then the client may invest in what I have just said and flesh it out. If my counter-transference is not accurate (or I have just hit an area that the client is not ready to go into just yet) then the client may tell me he doesn’t know what I mean, making no investment in the interpretation at all.

In offering to understand the sometimes-terrible experiences that I will get from some clients, I’m working to get to a place where I can invite the client into be curious about what they might be responsible for. Usually this will be in the context of the problems that they are talking about in therapy – and sometimes what I have to say challenges the client’s beliefs. I try and do this with empathy … and without necessarily telling them how I am being impacted upon (we’re here to understand the process, more than we are to watch the content). At the same time, because I’m challenging the client’s defence when I do this, the client may wish to strengthen the defence and not wish to take responsibility for their unconscious part in this interaction. This will be OK.

But often I find I have allowed a client’s door to be opened a little further and more details about the client’s reasons-for-being-in-therapy come out. All this from working to understand the impact a client sometimes may have upon me.

In Closing.

Bullying has purpose.

When we’re faced with bullying we quickly recognise the pain that the bullied are suffering and our attention is pulled towards those who are suffering (incidentally, also neatly turning our attention away from the pain that the bully may be projecting outwards too – neatly falling in line with the bully’s unconscious intention).

I’d offer you the thought that the bully is in great need help and understanding too.